40. Conquest of India

"Turn, and the world is thine." —KIPLING.

It was now two and a half years since Alexander had entered Asia. The fall of Tyre had given him not only Syria, but Egypt too, and the command of the sea, in this part of the Mediterranean. For Egypt was not strong enough to withstand this world-conqueror, so Alexander was crowned king at Memphis, the old capital of the Pharaohs. Here he held athletic games and a contest of poets, to which the most famous artists came over from Greece. From Memphis he sailed down the river Nile and founded a city, which is still called by his name, Alexandria, the port of Egypt. The new lord of Egypt and Syria, with the whole coast-land now in his possession, then started for Persia once more, for the Shah was again preparing to oppose him.

A great battle was fought—one of the greatest on record of the ancient world. The Shah had once more to ride breathlessly for his life, his army was scattered to the winds, and thousands were made captive.

It seemed, indeed, that Alexander was invincible. Babylon submitted to him at once, Shushan, the old capital, fell without a blow, and the victorious monarch marched ever forwards. The death of the Shah of Persia put fresh power into his hands. It was the task of his life to spread Greek ideas in the East: the best way to do this seemed to be, to become king of the East, according to Eastern ideas. So he surrounded himself with Eastern forms and pomp; he married a Persian wife; he dressed in the white tunic, and wore the Persian girdle, common to the great Eastern rulers.

This change was highly unpopular with his countrymen.

One night at a feast in one of the Persian fortresses, Clitus, the foster-brother and dear friend of Alexander, suddenly sprang up and began to abuse the king. They had all been drinking the strong wines of the country, and stung by the taunts of Clitus, Alexander rose. He snatched a spear, and in a sudden fury dashed it into his foster-brother. Clitus sank to the ground—dead. An agony of remorse followed for Alexander; for three days he lay in his tent, neither sleeping nor eating, till at last they roused him.

"Is this the Alexander, whom the whole world looks to, lying here and weeping like a slave?" cried one of his friends, as he beheld the prostrate form of the king.

Alexander now turned his eyes towards India, still to the outer world, an unknown land. Strange stories of its wonders, had reached the Greek invaders—stories of monster ants, who turned up gold-dust from the vast sand deserts; stories of men clothed in garments, made of plaited rushes, like mats; of trees that bore wool, instead of fruit; of lakes full of oil; of giants, dwarfs, and palm-trees that touched the skies.

Alexander and his army crossed the barriers of the Hindu Kush mountains, and entered the plains, through which flowed the river Indus. He had again passed from one world into another, a world which was to remain unknown for twenty centuries after the days of Alexander, until the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope should open out a sea-path to India.

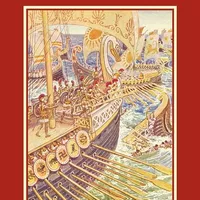

Crossing the Indus by a bridge of boats, he found himself in the district, now known as the Punjab, where five rivers meet. On the opposite bank of one of these rivers a powerful Indian king, named Porus, disputed his advance. A battle was fought, in which the sight and smell of the Indian elephants, on which King Porus's men were mounted, frightened the Persian horses. Finally, however, Alexander won. The vanquished Indian king was brought before him; he was very tall and majestic, and his bravery in battle had excited the admiration of the king. He inquired of Porus how he would wish to be treated.

"As a king," was the stern answer. "And have you no other request?" asked Alexander.

"No," answered Porus, "everything is included in the word king." So struck was he with this answer, that Alexander restored him his kingdom.

It was soon after this battle, that Alexander lost his beautiful horse Bucephalus, the one he had tamed as a boy, and which had carried him ever since. The poor beast died of age and weariness, and the king built a city, to its memory, on the banks of the river; which monument survives today—the city of Jalalpur.

Alexander longed to press on, and see all the wonders of India and the great river Ganges, but the Macedonians were weary of the march and absolutely refused to go another step farther. Their clothes were worn out, and they had to wrap their bodies in Indian rags; the hoofs of their horses were rubbed away by the long rough marches; their arms were blunted and broken. And the king, with unexplored lands yet before him, had to turn back.

He reached Babylon in the spring of 324, and at once began to fortify it, as the capital of his new and mighty empire. Here he held his court, seated on the golden throne of the Persians, with a golden canopy studded with emeralds and precious stones. Here he received people from every known country. Here he stood at the highest point of glory, knowing not, how near the end was.

While he was preparing for the conquest of Arabia, he was taken with a violent fever; he lay in bed eagerly discussing details, but he grew rapidly worse. In the cool of one June evening, while the fever was yet raging, they carried him to the river and rowed him across to a garden villa. As he grew worse they took him back to the palace. One by one the Macedonian soldiers filed past the bed of their young and dying king; he was too ill to speak to them. A few days later, Alexander the Great lay dead at the early age of thirty-three.

Into thirteen years he had compressed the energies of a lifetime, for in that short time he had doubled the area of the world, as known to the Greeks of his day.