CHAPTER 8, part 1

CHAPTER 8

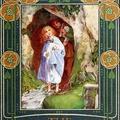

The Goblins

For some time Curdie worked away briskly, throwing all the ore he had disengaged on one side behind him, to be ready for carrying out in the morning. He heard a good deal of goblin-tapping, but it all sounded far away in the hill, and he paid it little heed. Towards midnight he began to feel rather hungry; so he dropped his pickaxe, got out a lump of bread which in the morning he had laid in a damp hole in the rock, sat down on a heap of ore, and ate his supper. Then he leaned back for five minutes' rest before beginning his work again, and laid his head against the rock. He had not kept the position for one minute before he heard something which made him sharpen his ears. It sounded like a voice inside the rock. After a while he heard it again. It was a goblin voice--there could be no doubt about that--and this time he could make out the words.

'Hadn't we better be moving? 'it said. A rougher and deeper voice replied:

'There's no hurry. That wretched little mole won't be through tonight, if he work ever so hard. He's not by any means at the thinnest place.' 'But you still think the lode does come through into our house?' said the first voice.

'Yes, but a good bit farther on than he has got to yet. If he had struck a stroke more to the side just here,' said the goblin, tapping the very stone, as it seemed to Curdie, against which his head lay, 'he would have been through; but he's a couple of yards past it now, and if he follow the lode it will be a week before it leads him in. You see it back there--a long way. Still, perhaps, in case of accident it would be as well to be getting out of this. Helfer, you'll take the great chest. That's your business, you know.' 'Yes, dad,' said a third voice. 'But you must help me to get it on my back. It's awfully heavy, you know.' 'Well, it isn't just a bag of smoke, I admit. But you're as strong as a mountain, Helfer.' 'You say so, dad. I think myself I'm all right. But I could carry ten times as much if it wasn't for my feet.' 'That is your weak point, I confess, my boy.' 'Ain't it yours too, father?' 'Well, to be honest, it's a goblin weakness. Why they come so soft, I declare I haven't an idea.' 'Specially when your head's so hard, you know, father.' 'Yes my boy. The goblin's glory is his head. To think how the fellows up above there have to put on helmets and things when they go fighting! Ha! ha!' 'But why don't we wear shoes like them, father? I should like it--especially when I've got a chest like that on my head.' 'Well, you see, it's not the fashion. The king never wears shoes.' 'The queen does.' 'Yes; but that's for distinction. The first queen, you see--I mean the king's first wife--wore shoes, of course, because she came from upstairs; and so, when she died, the next queen would not be inferior to her as she called it, and would wear shoes too. It was all pride. She is the hardest in forbidding them to the rest of the women.' 'I'm sure I wouldn't wear them--no, not for--that I wouldn't!' said the first voice, which was evidently that of the mother of the family. 'I can't think why either of them should.' 'Didn't I tell you the first was from upstairs?' said the other. 'That was the only silly thing I ever knew His Majesty guilty of. Why should he marry an outlandish woman like that-one of our natural enemies too?' 'I suppose he fell in love with her.' 'Pooh! pooh! He's just as happy now with one of his own people.'