Episode 224: Predictions of the Future from the Past [1]

Hello, hello hello, and welcome to English Learning for Curious Minds, by Leonardo English.

The show where you can listen to fascinating stories, and learn weird and

wonderful things about the world at the same time as improving your English.

I'm Alastair Budge, and today we are going to be

talking about Predictions Of The Future From The Past.

This episode is going to be released on December 31st of 2021, New Year's Eve.

And as we move from one year to the next, it's a time for

reflection, a time to think about the future, and what it holds.

So, in today's episode we are going to think about the future, but we're going

to look at predictions of what people thought their future would look like.

From predictions of a global population bomb to flying cars, buildings that travelled on

trains to living on Mars, we are going to take a long hard look at visions of the future.

First we're going to look at some predictions of the future that turned

out not to be correct, either not correct yet or not correct at all.

Then we'll look at some predictions that were eerily correct, people who correctly

predicted what today's world would be like despite their world looking very different.

And finally we'll take a look at some of the predictions of what some of the

most respected futurists, that is, men and women whose job is to predict the

future, think the future might hold for us, our children and our grandchildren.

OK then, Predictions Of The Future From The Past.

In general, as I hope will become clear as you listen to this episode, we humans are not very

good at predicting the future, at least we haven't been very good in the past hundred years or so.

Before this, especially before the Industrial Revolution, there wasn't nearly as much interest

in predicting the future, partly due to the fact that the future was thought to be pre-defined

by a divine being, by a God, but also as the world simply didn't change nearly as much.

If you took the average person living in let's say Rome in the year 100BC,

the year Julius Caesar was born, and transported them 1,000 years into the

future, into the year 900, would they be so surprised at what they found?

Of course there would be some surprises - the Roman empire would have disappeared and the

city of Rome would look very different, but people's day-to-day lives would be fairly similar.

Our time-traveller from 100 BC might easily adapt to life 1,000 years in the future.

If we think, however, of what life might be like for you or me,

transported into the year 3,021, in the 31st century, it is completely

unfathomable, it is impossible to think of what it might look like.

And even going back 100 years, to 1921, it was hard enough for people then to imagine

what a world might look like only 100 years in their future, where we are now.

This is, of course, due to the pace of technological change.

Technology, from the smartphone you might be listening to this on or the semiconductors in the

cars you drive, has created worlds that our predecessors had a huge amount of trouble imagining.

Our lives have been changed in ways that people simply didn't think possible.

And in many other ways, our lives have not changed, we

have not progressed as fast as people had predicted.

So, on that note, let's look at a few of the predictions from the past that have not come true.

Our first prediction comes from Thomas Robert Malthus, in

his 1798 essay "An Essay on the Principle of Population".

At this time the world population was around 1 billion and the

fast-growing population of England had reached 8 million people.

Long story short, Malthus believed that we were on course for a population explosion, and

that there would not be enough food to support the bulging, the fast growing, population.

This wasn't some crazy theory from an eccentric outsider.

Malthus was an influential and respected economist and scholar, and his book

contained detailed theory and calculations about why this was going to happen.

Malthus proposed that population growth happens more quickly

than the ability of a society to increase its food production.

So, because the population grows more quickly than the food supply, the amount of food

per person decreases, meaning that societies lose the ability to feed everyone, there

is famine, war and death, and then the population returns to its normal, correct size.

Essentially, there is a kind of doomsday scenario where the world runs out of food.

Fortunately, he has been proved incorrect so far.

Malthus failed to predict the impact of the Industrial Revolution, which came shortly

afterwards, and resulted in huge improvements in mankind's ability to feed itself.

Of course, some parts of the world do experience great famine and a lack of food,

but this is not due to an inherent inability of the world to feed its population.

There's more than enough food to go around, despite the global population being

almost 10 times what it was when Malthus was predicting this gloomy future.

This was in 1798, but his theory has continued to remain popular.

170 years later, in 1968 Paul Ehrlich, an economist at Stanford University,

followed in his footsteps with an explosive book called “The Population Bomb”.

The first sentence of the book read “The battle to feed all of humanity is over.”

Again, fortunately Ehrlich has not been proved correct, and the world population is set to peak at

around 2064, so the current view is that it is not population growth per se that we have to fear.

On the subject of sociological predictions by economists, while it is of course good news that the

predictions of Malthus and Ehrlich have been proved incorrect, no doubt many of us feel slightly

disappointed that one prediction of the economist John Maynard Keynes hasn't yet come to fruition.

Writing in 1930, in an essay called "Economic Possibilities For Our Grandchildren”, Maynard

Keynes wrote that when his children would be grown up people would work just 15 hours a week.

The logic behind this was that productivity gains would mean that we simply didn't

need to work any more than 15 hours, because automation and mechanisation would mean

that after 15 hours of work we would be able to produce enough to meet our needs.

Now, if you are the sort of person who does only 15 hours of work a week, well done.

It's safe to say that for the majority of the world

population, our working weeks haven't got any shorter.

In fact, for many people it's the opposite.

The technologies that people thought would make them more efficient

are actually blurring the boundaries between work and leisure.

If you have your email on your phone and your boss expects you to read and

respond to emails in the evening and on weekends, you are probably working

longer hours than someone did in the era of Maynard Keynes, where you would

leave your desk at 5pm on a Friday and not return until 9am on a Monday.

And while there are constant promises that new technologies and automation will

allow us to lead more fulfilling working lives, where tedious administrative work is

performed by technology, despite all of the technological advances that have been made

in the almost 100 years since Maynard Keynes prediction, we are not working any less.

And in some cases, we're working a lot more.

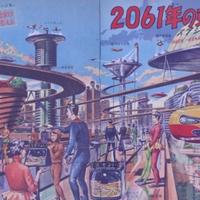

Now, when it comes to the more fun, wacky, strange predictions, some

of my favourites involve the design of cities and urban environments.

In Europe of the 18th and 19th centuries there had been mass migration to the cities.

Before 1600, it's estimated that less than 5% of the world's population lived in urban environments.

By 1800, it was 7%; and by 1900 it had more than doubled again, increasing to 16%.

Western Europe was ahead of the curve here.

In 1700, 13% of the population lived in cities, in 1800 it was 21% then by 1900 it was 41%.

Understandably, if it seemed inevitable that society was becoming

urban, people wondered what these cities of the future would look like.

You've probably seen artists' impressions of cities of

the future having flying cars and trains in the sky.

In 1900 there were a series of postcards created by a German chocolate factory

named Theodor Hildebrand & Son, which showed worlds and cities of the future.

Some particularly interesting ideas included having a ship that would

move seamlessly from the water onto a train track, and turn into a train.

It also envisioned entire houses or buildings that would be able to move on train tracks, as

well as humans being able to have personal flying machines, essentially giving themselves wings.

Another interesting urban vision was that entire cities would have roofs, that

there would be huge coverings that would go over cities and protect them from rain.

They also imagined a world in which you wouldn't have to walk anywhere to go around the city.

Instead, the pavements would move on rails, so it would be a little bit like being in an airport.

But, almost all of these predictions from only 121 years ago have not come true.

And even moving into the more recent future, anyone who is over the age of 30 or so will

no doubt remember the Millennium Bug, the fear in 1999 that when the clocks changed from

23:59 on December 31st of 1999 to midnight, to 00:00, in the year 2000 there would be some

huge collapse as computer systems wouldn't be able to manage the change of date correctly.

There were predictions that it could cost the global economy anything from

$400 million to $600 billion to fix, there were stories of people stockpiling

food, water, and guns in preparation for some kind of armageddon and then...

it was actually all ok in the end.

Now, while it might be easy to look back at some of these predictions and think, “how ridiculous

- did people actually believe that?”, there have been plenty of predictions that might have

seemed completely wacky and unrealistic at the time, but are now part of our daily lives.

Nikola Tesla, the Serbian-American inventor and electrical engineer who was

born in 1856 was one person who had an uncanny ability to predict the future.

He wrote, “As early as 1898, I proposed to representatives of a large manufacturing

concern the construction and public exhibition of an automobile carriage which, left to

itself, would perform a great variety of operations including something akin to judgement”.

By an automobile carriage, he's talking about a car, and when he says “left

to itself would perform a great variety of operations involving something

akin to judgement”, he's essentially saying it would be able to drive itself.

So, this was over 120 years ago, but there is Tesla predicting the creation of the self-driving car.

Yes, I hear you say, self-driving cars aren't here yet, but they are certainly on the way.

And there are plenty of Tesla's predictions that are already here.

In 1926, which was the same year that the first transatlantic

telephone call was made, Tesla imagined where this might lead.

He wrote, and I'm quoting directly here: “When wireless is perfectly

applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in

fact it is, all things being particles of a real and rhythmic whole.

We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly, irrespective of distance.

Not only this, but through television and telephony we shall see and hear

one another as perfectly as though we were face to face, despite intervening

distances of thousands of miles; and the instruments through which we will be

able to do this will be amazingly simple compared with our present telephone.

A man will be able to carry one in his vest pocket.”

Now, a wireless instrument through which you can communicate with

anyone, irrespective of distance, which you carry in your vest pocket.

Perhaps that's exactly the device with which you are listening to this now, a mobile phone.

Indeed, you could say that the most incorrect part of Tesla's prediction is that he is

assuming that people in the future would still have the same fashion sense as they did in 1926.

Now, of course, significantly fewer men wear suits and therefore

would have a vest pocket to put this special device into.

We could go on and on with Tesla, and he correctly predicted the need

for us to protect our water supply, he correctly predicted WiFi and

wireless internet, he even predicted what we would now call “drones”.

And his predictions weren't only about specific types of

technology, but how societies would change relating to technology.

He wrote, and again I'm quoting directly here:

“Today the most civilized countries of the world spend a

maximum of their income on war and a minimum on education.

The twenty-first century will reverse this order.

It will be more glorious to fight against ignorance than to die on the field of battle.

The discovery of a new scientific truth will be more important than the squabbles of diplomats.

Even the newspapers of our own day are beginning to treat scientific

discoveries and the creation of fresh philosophical concepts as news.

The newspapers of the twenty-first century will give a mere ”stick” in

the back pages to accounts of crime or political controversies, but will

headline on the front pages the proclamation of a new scientific hypothesis.”

Again, this might seem obvious with the benefit of hindsight, but Tesla was

born in 1856 and died in 1943 - his entire life was dominated by warfare.

He would no doubt be disappointed to see how much countries still spend

on war, but he would be pleased to see an increasing spend on education.

Now, this brings us onto some predictions people are making today about our futures.

Keeping in mind that what might have seemed possible and probable 100 years ago, for example

having roofs on cities, has not transpired, it's not happened, and something that might

have seemed completely impossible, such as being able to talk to anyone, anywhere in the

world, has proved possible, here are some ideas about what the future might look like.

I'll leave it to you to decide whether you believe these might come true.

So, one famous futurist and American theoretical physicist, Michio Kaku, believes that in the future

cancer simply won't exist, and it will be as much of a problem for mankind as the common cold.

He believes that technology in things like our toilets will be constantly monitoring our bodies,

so that at the first sign of a cancerous cell, it would be able to be treated before it multiplies.

He goes so far as to say that the word “tumour”, which are the groups of abnormal

cells often caused by cancer, would simply disappear from the English language.

Further afield, there are plenty of people who believe that our

future is multiplanetary, that humans will live on other planets.

Elon Musk has made no secret of his belief that humans need to colonise Mars,

and is busy building companies that will go there and build a new civilisation.

And, on a more recent note, you may well have seen the announcement from

Facebook, or should I say Meta, about its vision for the not-so-distant future.

Mark Zuckerberg, the company's founder, believes that one future has people spending

long periods of time living in virtual worlds, further blurring the line between the

physical and digital world, allowing people to exist in this Metaverse, as he calls it.

Mark Zuckerberg has been right about a lot of things that people

thought he was crazy about at the time, from buying Instagram to

WhatsApp, so this is no doubt a future that he thinks is very probable.

Now, before you go, I want to share some of the worst predictions with you,

some that have simply proved to be incredibly incorrect, just in case you need

any more evidence that we humans are awful at imagining the future, even those

people who are clearly very intelligent and good at understanding the present.

So, we are going to do a little mini-Olympics of bad predictions, and we are going to award

the bronze medal, the third place, to Thomas Watson, the chairman of IBM, the technology

company, who said in 1943, "I think there is a world market for maybe five computers. ".

Then, the runner up, our silver medal, the second place, goes to H.

M.

Warner, from Warner Brothers, the film production company, who said in

1927, in the era of silent films, "Who the hell wants to hear actors talk? ".

And the gold medal goes to Charles H.

Duell, Commissioner of the U.S.

Office of Patents.

Now, some people think this is an urban legend, but the story goes that

in 1899 he said “Everything that can be invented has been invented.”

Whether or not Duell actually said that, it is anyone's guess, but it is certainly

true that in general we are simply very bad at predicting what lies ahead of us.

So, if we go back to the start of the episode, to our man born in 100

BC in Ancient Rome, he probably wasn't so concerned with what the future

might contain for him, as the past wasn't so different from his present.

It was only really as the world started to change so quickly, and the society and

environment we lived in changed that we started to really think about what lay ahead.

Obviously, there are some pretty frightening predictions about the future, but there is

a lot to be excited about, and one can only hope, and indeed take actions, that reduce

the likelihood of the gloomiest of predictions and bring in a brighter future for us all.

Ok, that is it for today's episode on Predictions Of The Future From The Past.

If you are listening to this episode on the day it comes out, on

December 31st of 2021, then I hope you have a very Happy New Year's Eve.

And if you are listening to this episode from 2022, from the future, then I hope it is bright.

As always, I would love to know what you thought of this episode.

What are some other interesting predictions of the future from the past that you know about?

What are some predictions for the future that interest you, that scare

you, or that you just think are particularly ridiculous or improbable?

I would love to know, so let's get this discussion started.

You can head right into our community forum, which is at

community.leonardoenglish.com and get chatting away to other curious minds.

You've been listening to English Learning for Curious Minds, by Leonardo English.

I'm Alastair Budge, you stay safe, and I'll catch you in the next episode.